No Thomas Mann this week…Just a Revered Novel from 1952

- Gail Wilson Kenna

- 3 days ago

- 2 min read

Yesterday I needed to read something for a dispirited self, and I went downstairs to locate a tiny hardcover in my Hemingway collection. Published in 1952, this college edition of Old Man and the Sea has 127 pages. The cover is two-tone blue like the Caribbean Sea. Near the center is a shiny fish drawn in gold and below it is Ernest Hemingway’s signature in gold.

The fish remains unnamed, as if unique. It is neither a Marlin or Tuna. The old man, Santiago, “saw him first as a shadow that took so long to pass under the boat that he could not believe its length. “No,” he said. “He can’t be that big.” But he was that big and at the end of his circle he came to the surface only thirty yards away …his tail out of the water.”

Santiago meant a lot to me the summer of 1957 before I began high school. The novel came into my hands by accident and it’s too long to explain how. But Santiago represented Hemingway’s maxim in French: "il faut (d’abord) durer ..” One must (first) endure. Yet four years later on July 1st in 1961, a month after high school graduation, the national news shocked me.

Hemingway had shot himself in Ketchum, Idaho. This meant his French maxim about endurance was succeeded by another: “il faut (après tout) mourir.” One must (after all) die.” At eighteen I could not process Hemingway’s suicide, not given his code about surviving. Nor did I understand then his masculine view of life. Yet Santiago reflected what my father tried to instill in me about not being a quitter. When the going gets tough, the tough get going. It was not whether you won or lost; it was about how you struggled. This was the human test of character, and it needed to be guided by moral consciousness, not self-interest.

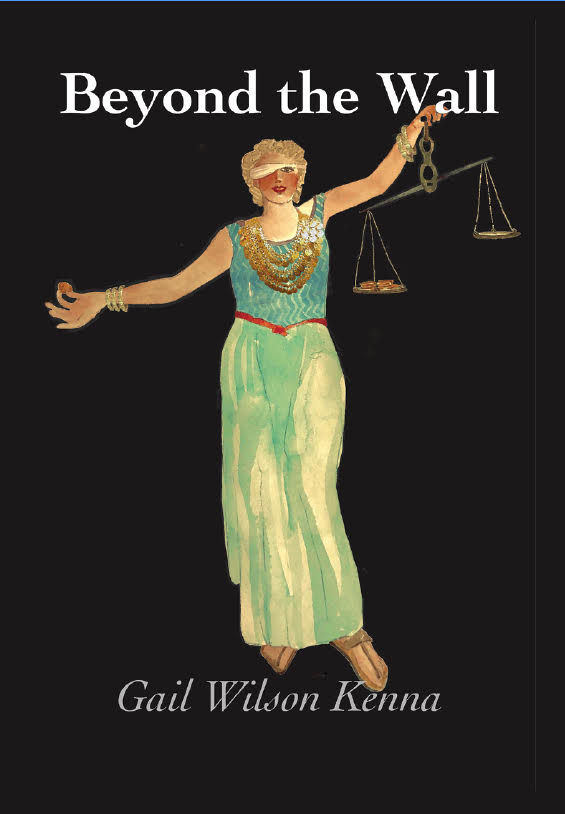

Still, Santiago loses to the sharks. Too many voracious ones to save his magnificent fish from mutilation. Yet there was nobility in both this old man and the boy who reveres him. Reading the novel yesterday, I again loved the simplicity of this story and its economical and clear language. I’d read the novel often during four years in Venezuela when my spirit needed regular infusions of endurance. Thirty years ago, this summer, the Kenna family left Venezuela. I assumed we were leaving behind an oligarchy, one rife with corruption in the land of Napoleonic law. In this legal system, someone is assumed guilty until proven innocent. In my heart and mind, I believed I was returning to a country that believed in its Constitution and the fairness of our judicial system, when guilt must be proven under the law, in contrast to Venezuela’s Lady Justice.

Next week: Thomas Mann as promised, the brilliant writer who escapes Germany’s Third Reich….

Comments